‘Meester Dean,’ says Macarena. ‘How you write ‘leetoldoh’ een Eenglish?’

It’s Monday morning, and the kids are working on their ‘What I did at the weekend’ pieces.

And not for the first time, I’m stumped.

Leetoldoh? What the hell is one of those?

Guessing that it’s probably spelled ‘litoldo’, I google wordreference.com, and trawl for a quick translation.

Nothing. Nada, as they say around here.

‘Leetoldho?’ I say.

‘Yes, yes. My friend have eet. Ees blanco. She bring to my casa.’

Another clue. Mac’s friend has a leetoldoh, and it’s white, and she brings it to Mac’s house.

I’m not much further on.

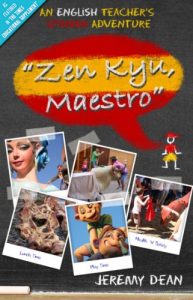

Jeremy Dean is flummoxed, but then he’s come to expect that.

He is an English teacher, teaching Spanish children, in English, in a school in Spain.

Confused? He certainly is.

Not long ago, Jeremy and his wife, Linda – both 25-year-veterans of the English education system – decided it was time for a change. So they quit their nice, safe jobs and moved to an ‘immersion school’ in a picturesque town some distance north of the Costas.

The financial storm is just about to break, none of the kids can speak a word of English, and no-one seems to know what’s going on…

‘Never mind,’ I say, brightly. ‘Just write it in Spanish. I’ll get someone to translate it later.’

‘¿I write eet en español?’ She looks confused.

‘Yes, I don’t know the English.’

‘But leetoldoh ees eengleesh.’

‘Leetoldoh is English?’ I say.

‘¡Claro!’ It’s a great word, claro. It means, ‘of course’ or ‘clearly’. It doesn’t always carry a ‘You dumb ass!’ implication. You need a certain intonation for that and a particular look in your eyes. If you could hear and see Macarena now, you’d know what I mean.

‘So… how do you say leetoldoh in Spanish?’ I say.

‘Perro pequeño.’

‘¿Perro pequeño?’ I repeat. ‘Little dog?’

She shrugs. Claro. Dumb ass.

‘You want me to spell “little dog” in English?’

‘¡I say eet!’ she protests, as if I’ve accused her of not saying eet.

This is the diary of Jeremy Dean’s first year in this bizarre system (a system he comes to love, along with the children), complete with endless confusion, misunderstandings, a heart attack and an eye-opening insight into a Spain the average Briton never sees.

AS FEATURED IN THE TIMES EDUCATIONAL SUPPLEMENT

It’s Monday morning, and the kids are working on their ‘What I did at the weekend’ pieces.

And not for the first time, I’m stumped.

Leetoldoh? What the hell is one of those?

Guessing that it’s probably spelled ‘litoldo’, I google wordreference.com, and trawl for a quick translation.

Nothing. Nada, as they say around here.

‘Leetoldho?’ I say.

‘Yes, yes. My friend have eet. Ees blanco. She bring to my casa.’

Another clue. Mac’s friend has a leetoldoh, and it’s white, and she brings it to Mac’s house.

I’m not much further on.

Jeremy Dean is flummoxed, but then he’s come to expect that.

He is an English teacher, teaching Spanish children, in English, in a school in Spain.

Confused? He certainly is.

Not long ago, Jeremy and his wife, Linda – both 25-year-veterans of the English education system – decided it was time for a change. So they quit their nice, safe jobs and moved to an ‘immersion school’ in a picturesque town some distance north of the Costas.

The financial storm is just about to break, none of the kids can speak a word of English, and no-one seems to know what’s going on…

‘Never mind,’ I say, brightly. ‘Just write it in Spanish. I’ll get someone to translate it later.’

‘¿I write eet en español?’ She looks confused.

‘Yes, I don’t know the English.’

‘But leetoldoh ees eengleesh.’

‘Leetoldoh is English?’ I say.

‘¡Claro!’ It’s a great word, claro. It means, ‘of course’ or ‘clearly’. It doesn’t always carry a ‘You dumb ass!’ implication. You need a certain intonation for that and a particular look in your eyes. If you could hear and see Macarena now, you’d know what I mean.

‘So… how do you say leetoldoh in Spanish?’ I say.

‘Perro pequeño.’

‘¿Perro pequeño?’ I repeat. ‘Little dog?’

She shrugs. Claro. Dumb ass.

‘You want me to spell “little dog” in English?’

‘¡I say eet!’ she protests, as if I’ve accused her of not saying eet.

This is the diary of Jeremy Dean’s first year in this bizarre system (a system he comes to love, along with the children), complete with endless confusion, misunderstandings, a heart attack and an eye-opening insight into a Spain the average Briton never sees.

AS FEATURED IN THE TIMES EDUCATIONAL SUPPLEMENT